2,000 Years of Tax Fraud—and How to Stop It Now

ECONOMIC VISION

4/16/20254 min read

Bureau of Society and Transformation

Who We Are:

The Economic Nations champions global unity through economic collaboration, focusing on sustainable growth, reducing inequalities, and enhancing global relationships for mutual prosperity and peace.

______________________________________

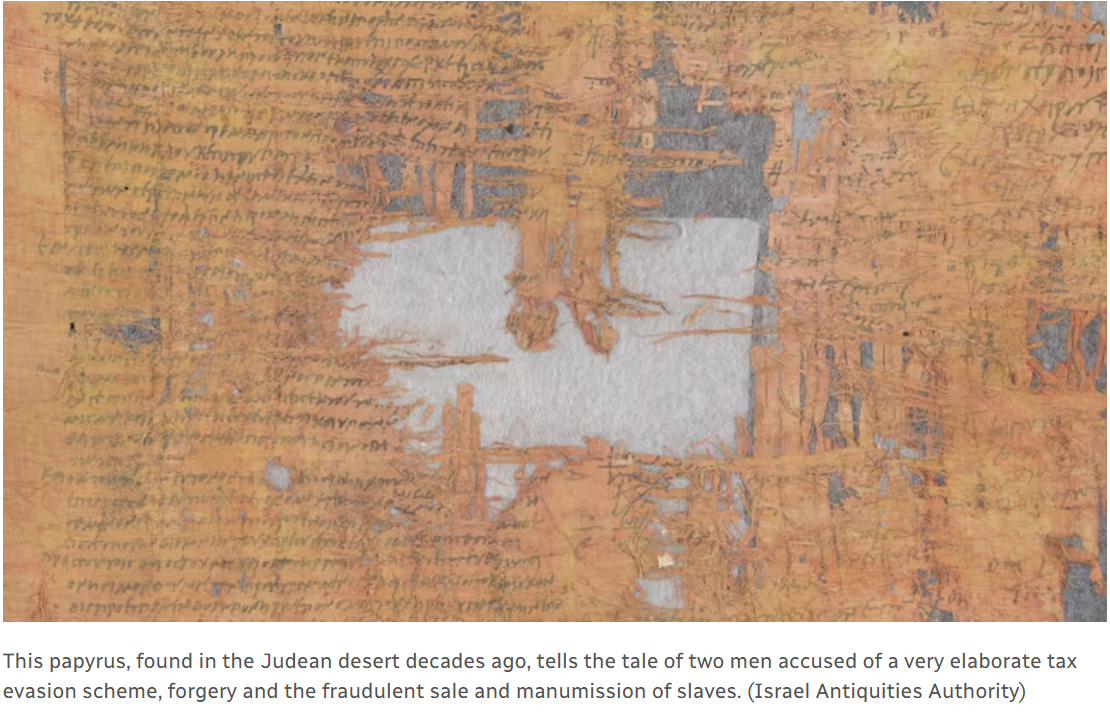

Tax evasion is not a modern phenomenon. It is a recurring theme in the long arc of human civilization, shadowing the evolution of tax systems from Mesopotamia to Rome. If anything, history is rich with lessons for modern policymakers trying to fine-tune tax laws. From Sumerian clay tablets to a 1,900-year-old Roman papyrus found in the Judean Desert, the evidence is clear: whenever governments have taxed, citizens have schemed to avoid. The critical question is not whether tax evasion will occur—it will—but how systems can be designed to reduce it effectively and fairly.

The ancient Roman case of Gadalias and Saulos, recently reconstructed from a Greek-language papyrus unearthed near Nahal Hever, is a striking example. These two men orchestrated a slave-sale scam to sidestep a 4% tax levied on such transactions. By falsifying documents to show that slaves were sold across provincial lines—when in fact they remained in the same hands—they created “ghost transfers,” effectively erasing the slaves from Judean tax rolls without triggering registration in Arabia. This was more than an isolated act of deceit. It was a calculated attack on the fiscal apparatus of the Roman state, carried out with legal sophistication, document forgery, and bribery of local officials. The Roman authorities responded with severity—through judicial hearings, threats of exile, and possibly death—showing the high stakes involved in maintaining the empire's financial backbone.

But ancient Rome was not alone in its tax dilemmas. In Mesopotamia, clay tablets from Uruk and Lagash recorded not only tax receipts but also evasions and penalties. The existence of these records, dating as far back as 3,300 B.C., confirms that audit and compliance mechanisms were already in place five millennia ago. The Babylonians codified tax obligations in stone through Hammurabi’s Code, including proportional dues, land-based levies, and penalties for concealment. Early Chinese states, as seen in Qin and Han bamboo slips, documented detailed tax rolls, harvest-based assessments, and household obligations with surprising bureaucratic rigor. Egypt’s nilometers turned flood predictions into tax forecasts, linking natural cycles with fiscal expectations in a way that still echoes in today’s climate-sensitive economic policies.

What do these ancient systems have in common? They were highly motivated to extract revenue but remained constrained by administrative capacity, political stability, and public tolerance. Those constraints remain today. Every tax system walks a tightrope between enforcement and legitimacy. Go too soft, and evasion becomes rampant. Go too hard, and resentment breeds instability. The Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt understood this well: they offered tax exemptions to temples to prevent revolt, balancing state control with cultural diplomacy. This isn’t unlike modern states offering exemptions and reliefs to quell dissent or stimulate compliance.

The enduring nature of tax evasion points to a deeper reality—taxes are not just economic tools, they’re political expressions of power and consent. The visibility of wealth extraction, and the perceived fairness of the system, often determine whether people comply or resist. Ancient Assyrian reliefs depicting tribute from conquered lands were not just art—they were propaganda, legitimizing taxation as a symbol of imperial dominance. In contrast, the Rosetta Stone captures the subtler side of tax policy: selective exemptions to maintain societal peace.

Have You Read:

Today’s tax regimes have the benefit of digital infrastructure, forensic accounting, and multinational treaties. Yet, as the Roman slave-sale scam illustrates, evasion often thrives not because systems are outdated, but because evaders exploit the complexity of laws, the silos between jurisdictions, and weak enforcement at the margins. Gadalias and Saulos manipulated interprovincial boundaries in the Roman Empire; today, corporations shift profits to tax havens through transfer pricing. The structure is different, but the strategy is the same: obscure the transaction, fragment the trail, and disappear from the books.

This is where history offers its most urgent lesson. Enforcement is essential, but no tax system can rely on force alone. What ancient Rome had—legal clarity, documentation protocols, regional oversight, and a credible threat of punishment—is still the foundation for modern compliance. But to go further, modern systems must embrace transparency, data integration, and interagency cooperation. Just as Dr. Dolganov had to reconstruct the fraud by viewing it from both the fiscal administrator’s and fraudster’s lens, modern regulators need a 360-degree view of taxpayer behavior, using AI, cross-border data sharing, and real-time analytics.

Moreover, systems need to be perceived as fair. When elites bribe their way out of tax obligations—as Gadalias tried to do—public trust erodes. Unequal enforcement becomes a bigger threat than evasion itself. Tax reforms that ignore this lesson often fail. For instance, the G20-led OECD initiative to set a global minimum corporate tax of 15% stems from this historical understanding: unless major economies close the escape routes together, compliance will remain selective and exploitative.

In short, history doesn’t just hold lessons—it holds mirrors. We see ourselves in Gadalias’s schemes, Hammurabi’s codes, and the priestly exemptions of Ptolemaic Egypt. The tools have changed; the tension between obligation and avoidance has not. The true path forward lies in blending the administrative rigor of the ancients with the ethical and technological expectations of today.

If there’s one takeaway, it’s this: tax systems don’t just reflect the strength of a government—they define its relationship with its people. The more we study the failures and innovations of the past, the better we can build systems that people respect, rather than outwit.

Contacts

enquiry@economicnations.org

(xx) 98-11-937-xxx (On verification)